There’s nothing about the cancer journey that’s easy.

This should go without saying. We all know by now how a cancer diagnosis is fraught with more negativity than anything else.

So let’s all agree right now that we’re not going to judge the ways other people might handle that journey.

It seems almost ridiculous to have to write that, but I’m frequently surprised by the insensitivity of those who may not have experienced cancer firsthand. Whether you’ve been diagnosed yourself or suffered along with a friend or family member who’s diagnosed, you know all too well what I’m talking about.

Everyone offers advice. We all have a story. And if you’re one of the people (not me) who chooses to keep your diagnosis very quiet, you deserve exactly that – to be left alone in this difficult time.

On the other hand, if you’re determined to be totally transparent and seek support from everyone in your particular circle, you should get exactly what you need – lots of understanding and support.

Perhaps you’re somewhere in the middle – a few friends to know so they can keep you in their thoughts and prayers, but not the entire social media spectrum. Maybe you’re nervous about getting too much attention or undue pity.

Regardless of what a cancer patient chooses, our job is to leave the judgment at home.

Because just like in life, until someone directly asks you for specific help or your opinion, you can safely assume they don’t want either.

There’s this weirdness about cancer, perhaps because it’s so widespread and so publicized. Everyone thinks they know the answers. They all have an opinion. Stories abound.

I wrote a chapter in my book about running into someone at church while I was smack dab in the middle of treatment. This person caught me in the commons after Sunday service and began a long story about a child who had cancer that turned into a serious arterial bleed at home “. . .and there was blood everywhere, on the bed, on the floor. . .” that turned into emergency surgery that turned into. . .well, I can’t remember all the gory details. I hope there was survival, because I turned my brain off at the words “emergency surgery.”

What I remember most vividly was that I was first frightened and then sickened by this person’s assumption that I wanted or needed to hear a scary story about cancer when I was facing my third chemo treatment in two days. I was finally feeling slightly human and being regaled with a near death treatment experience was the opposite of what I wanted in that moment. I wanted comfort and care and love, not fear. I had plenty of my own fear. I was already neurotically obsessed with negative possibilities.

So, leave the scary stories and the marginal advice out of your conversations with cancer patients. They have plenty of fear already. You don’t need to add to it.

And if they don’t want you to tell a soul that they’re sick, if they say, “Please keep this under your hat,” do what they ask.

No judgment ever. That’s my best advice for how to talk to a cancer patient.

Your job is to say, “I’m here, thinking about you.” Not “OMG, I just heard the worst story about so and so’s battle with cancer!”

(By the way, you’ll notice that when I talk about cancer diagnoses, I don’t use the word “fight.” Cancer camps are divided on how to refer to what a patient goes through, but saying that I was in a “fight” somehow felt to me like I was giving cancer more power than I wanted to. More on that in another post.)

I’d love to hear comments from those of you who had someone judge your journey.

Thanks for checking in!

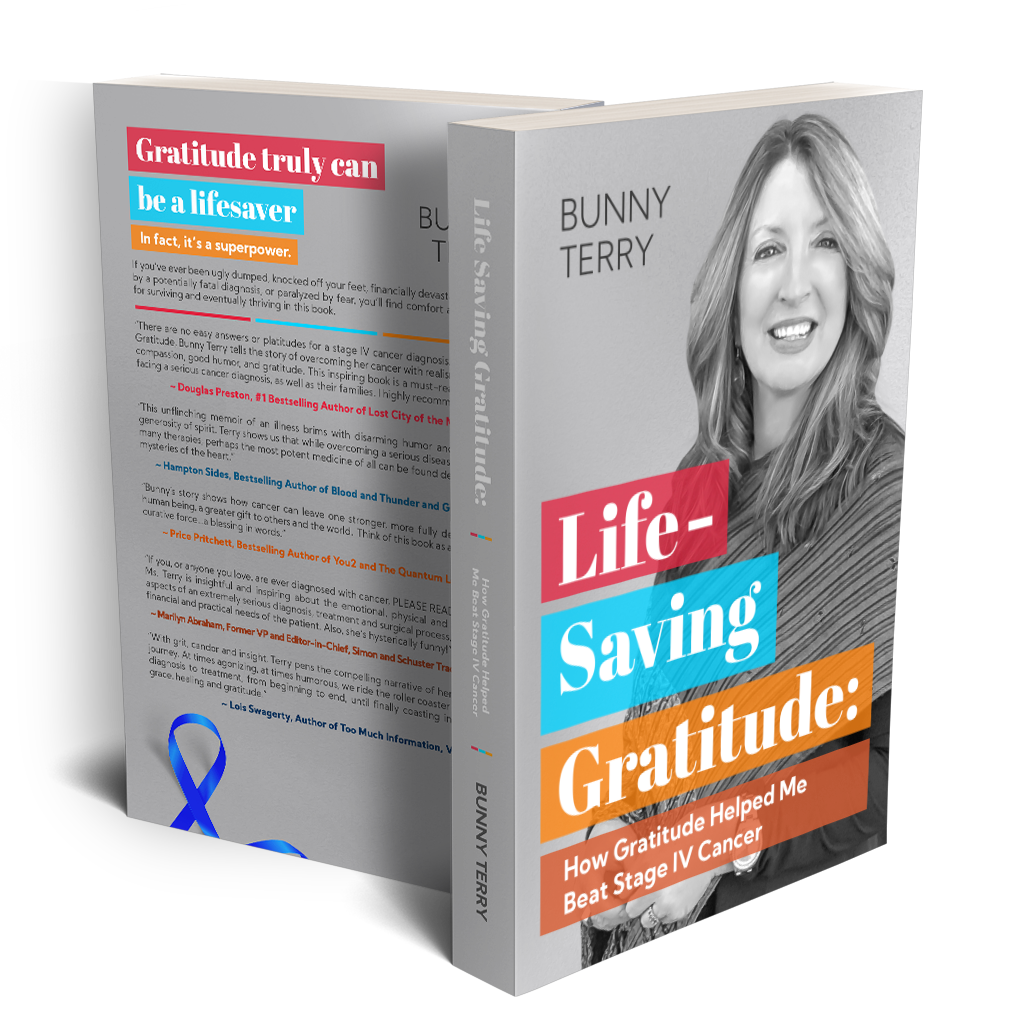

Bunny Terry is a native New Mexican who grew up on a farm in northeastern New Mexico. Her first writing job was typing stories on index cards on her family’s Underwood, stories that were uncannily like the ones she read over and over in O Ye’ Jigs and Julips, her favorite childhood book. No one thought to save those index cards for posterity, although there is the theory sarcastically circulated by her siblings that they will certainly be worth millions someday.

Bunny Terry is a native New Mexican who grew up on a farm in northeastern New Mexico. Her first writing job was typing stories on index cards on her family’s Underwood, stories that were uncannily like the ones she read over and over in O Ye’ Jigs and Julips, her favorite childhood book. No one thought to save those index cards for posterity, although there is the theory sarcastically circulated by her siblings that they will certainly be worth millions someday.

This also makes me think of when another (know-it-all) church person criticized you for eating sugar while in treatment. Like you didn’t have enough to worry about so you should give up the simple pleasure of a piece of chocolate every once in a while?! I couldn’t believe someone, who wan’t your doctor, would dare to tell you how or what to eat while you are living through something traumatic and also getting pumped full of poison every other week! The nerve of some people…

It was a crazy time. And it seems like folks are especially quick to tell a cancer patient what they should and shouldn’t eat.